Excerpt

Chapter 4

Picturing Mate as Rural in Argentina and Uruguay, 1870s–1920s

Outside a simple adobe home, a woman heats a fire to warm the water she has carried from a distant well. She spoons dusty green yerba into a mate made from a gourd seasoned by many previous mates. When the water is hot, she pours some of the water into the vessel and takes a sip to ensure that the yerba has not clogged the straw. The first sip fills her mouth with a few stray leaves and the smoky, bitter flavor of the hot infused water. But this mate is not for her. She brings the mate and the kettle outside. There, she sees her common-law husband—who many would call a gaucho—astride his horse, preparing to depart. She infuses the mate with hot water once more and hands it to him. He takes a sip before galloping away.

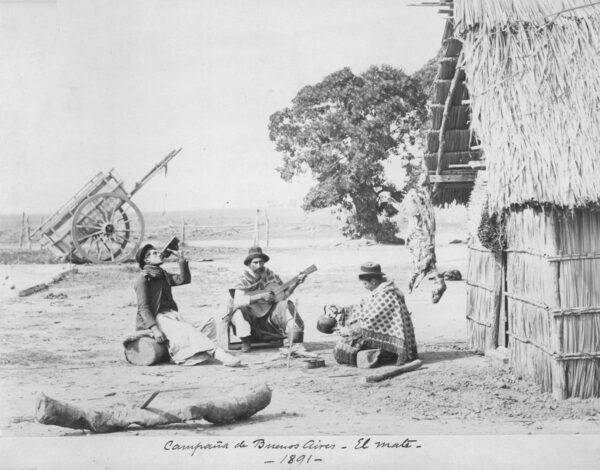

In the countryside, this man and other gauchos like him spend their days rustling cattle. When they need a respite from their work, they gather together around a campfire. This being far from home, there is no woman present to make the men’s mates, so the youngest man does the job. He tends the fire and heats the water in the kettle. Like the woman, he tastes the first mate to make sure the bombilla is unclogged, the water hot, and the mate ready to share. Then, he passes it to an older man, who takes a break from playing guitar to slurp the hot infusion. Another man holds a flask of liquor to his lips. The guitar player hands the mate back to the young man, who pours the water into the mate and passes it to the man with the flask. The men continue in this way for hours.

These two idyllic scenes of rural mate drinking became increasingly familiar to people living in Argentina and Uruguay around the turn of the twentieth century. Inspired in part by earlier illustrations of rural life, Argentine photographer Dr. Francisco Ayerza first captured them on camera in the 1890s (figs. 4.1 and 4.2).

A leader in amateur photography in Argentina, Ayerza took about a dozen photographs featuring mate. In all but one, where a woman sits at a dance drinking a mate, men are pictured as mate drinkers, highlighting nostalgic associations of self-sufficiency, male friendship, and leisure on the open plains. When present, rural women are featured as rural men’s mate servers—a dramatic shift from earlier compositions that showed Black and Brown mate servers attending White women or socializing over a round of mate. This was part of a larger turn from a feminine and urban vision of the lower Platine region in the early nineteenth century to a masculine criollo conception by its end.

How did women go from being envisioned as the preeminent mate drinkers in the colonial and early national era to either serving the mate or not being shown at all? What did this have to do with local elites’ new and sometimes conflicting visions for themselves as modern, European-style actors in South America? And how did the massive arrival of immigrants from Europe help foster tighter links—now pictured as traditional—between mate, rural masculinity, and national identity?